A Memoir of an Unusual Friendship

by Caroline Kennedy

I remember the moment so well. We were sitting across from each other, on red velvet banquettes, in a quiet corner of Annabel’s in Berkeley Square, indulging our taste buds in the nightclub’s famous marmalade ice-cream, when he suddenly blurted out:

“I think I’ve got cancer?”

The words hit me just as I was about to savour the last delectable spoonful. My mouth fell open as I jerked the spoon back.

“What?” I spluttered, “How do you know?”

A creamy globule shot directly from my lips, like an exploding bath bomb, across the mahogany and glass coffee table. He reached for his linen napkin and methodically wiped his cheek and then proceeded to mop the slowly-dripping substance from the lapel of his dark grey Savile Row suit. If nothing else, I thought, he should be impressed by my aim!

I have to say here that this wasn’t my first encounter with him. It was about a week later. And I couldn’t help thinking that a slingshot of half-digested marmalade ice cream across his face might not help forge a long-lasting friendship. But I was to be proved wrong.

Carefully, he smoothed a lock of thick greying wavy hair back from his forehead. A deliberate habit he had when he was trying desperately to think of what to say next.

“Yes, I’m sure of it, Caroline,” he lowered his voice almost to a conspiratorial whisper, leaning over the table towards me. “I’ve got a lump on my back, right here!”

He reached over and grabbed my hand, guiding it towards an area of his back just below his left shoulder.

“Feel it?” he asked, his dark eyes fixing on me anxiously.

My fingers gently prodded around.

I shook my head. “Nothing there,” I reassured him.

“But there is,” he insisted, “really, there is!”

He removed his jacket and placed my hand back in the same spot.

“There! Right there! Don’t you feel it?”

I had to admit then I could feel something. Though I wasn’t quite sure what.

“Yes. I think I can!” I said, not entirely convinced. “But why on earth would you think it’s cancer?”

“I just know it,” he replied, easing his arms back into his silk-lined jacket. “But don’t say anything to anyone! I don’t want this story to get out. Right?”

I nodded. This man I hardly knew was entrusting me with a secret. A big secret. Why would he do that? But then, again, knowing who he was, I could just imagine what gossip columnists around the world would have done with this choice bit of news if I let the cat out of the bag.

“So who’s the best surgeon in England?” he asked. “I need to make an appointment right away.”

“Well, I would imagine, the Queen’s physician,” I replied without hesitating. “She must have the best doctors, surely?.”

“What’s his name, do you know?”

It just so happened I did know. He was a Scot, a vague acquaintance of my mother and stepfather. For some reason his name had cropped up in conversation at a family dinner only recently.

“His name’s Andrew Semple,” I said.

He removed a well-thumbed leather notebook and gold Parker pen from his breast pocket and scribbled a note to himself.

“But, don’t worry,” he whispered reassuringly, as he returned the notebook and pen to his lapel pocket, “this doesn’t alter our plans. I’m still taking you to the Ferriers’ Masked Ball on New Year’s Eve. We can’t miss that, can we?”

I breathed a sigh of relief. I had always been curious about these legendary New Year’s Eve parties hosted by the famous Punch cartoonist, Arthur Ferrier, and his wife Freda. They had been the talk of London for well over a decade. It was said that every year people fought, tooth and nail, and offered exorbitant prices for an invitation. But the guest list was strictly handpicked by the Ferriers. And no amount of money could buy you entry.

“So,” he continued, “tomorrow I’m taking you to Angel’s Costumiers in Covent Garden and I’m going to hire you the most beautiful dress they have. You are going to be the Belle of the Ball. My belle of the ball.”

He took a long sip of milk from the crystal champagne goblet.

“You know what?” he smiled ruefully, twisting the fluted glass in his elegant fingers. “A glass of milk at Annabel’s costs more than a glass of milk at El Morocco!”

He was like that. It was another thing I had noticed about him. He could change the mood and the conversation in the bat of an eyelid.

“No, I didn’t know that,” I said. “Maybe New York has inferior cows!”

“But you’ll find out soon enough. You’re coming to New York with me and I’m going to take you to El Morocco!”

“You’re right,” I replied. “I am coming to New York – very soon. But not with you.”

True to his word, he did take me to Angel’s the following day. And, true to his word, he did rent the most beautiful dress in the shop for me – a magnificent gown designed by Cecil Beaton for his favourite muse, Vivien Leigh.

But, not true to his word, we didn’t end up going to the Ferriers’ New Year’s Eve Ball. Why? Because the increasing fear he had of the growing lump on his back was making him so paranoid that he spent the last week of December holing up in his house waiting for his appointment with Dr. Andrew Semple in the New Year.

And when that day came – and I went with him to the Harley Street surgery – the Queen’s physician took one look at the small lump below his left shoulder and announced, “You have an ingrowing hair, Sir. Do you want me to pluck it out?”

He didn’t see the humour in the situation. But I’m afraid I giggled uncontrollably. So I had missed out wearing the beautiful Cecil Beaton dress and being the belle of the Ferriers’ New Year’s Eve ball for something as life-threatening as an ingrown hair?

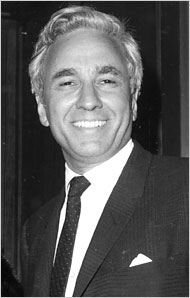

You may be wondering by now who was this man who treated me to marmalade ice cream at Annabel’s, who promised to make me the Belle of the New Year’s Eve Ball, who wanted to take me to El Morocco’s in New York and who almost died of fear from an ingrown hair?

I had met him less than two weeks earlier. I was having a night out at the Red Lion Pub in Mayfair. My best friend Ming was heading off for a job in New York. And a few of us were giving her a send-off. I was planning to follow her two months later so, in a way, it was a double send-off.

It was a Friday night, just before Christmas. The Pub was packed to the rafters. The stereo was playing “I saw Mummy Kissing Santa Claus”. I was distracted and didn’t see him approach.

“I’m George,” he said, extending his hand towards me.

“What?” I said.

“My name’s George!” he shouted with an evident transatlantic twang. “Want a drink?”

Before I could answer he had grabbed my arm and pulled me away from my friends and in the direction of the bar.

“I don’t drink!” I said.

“What?” he said, leaning in closer to me.

“I don’t drink!” I shouted above the cacophony of voices, the saturating music and the clink of glasses.

He laughed. “My kind of girl. Neither do I!”

He reached into his pocket and extracted a gold embossed cigarette case.

“Cigarette?”

I shook my head. “Don’t smoke either!” I shouted.

“My lucky night!” he laughed. “Neither do I! Just carry them for others!”

I didn’t often go to pubs. Didn’t see the point. I didn’t drink. I didn’t smoke. And I hated shouting to make myself heard. Made everything I said sound foolish, inconsequential or totally irrelevant. So, when he suggested leaving, I have to say I was tempted.

“Let’s get out of here!” He jostled me through the crowd towards the door.

“But my friends!” I protested. “I’m with some friends!”

“Bring them too,” he said. And then, after a pause, he joked, “I don’t bite, if that’s what you’re thinking!” He laughed.

I was hesitant. He seemed harmless enough. In fact, he seemed charming. But then, I thought, who goes around picking up strange girls in pubs and offers to take them home, all in the space of five minutes?

“Anyway,” he said, reading my mind. “I live just around the corner. So if you feel bored, threatened or you’ve had enough, you can always come back here!”

My friends swiftly demolished the dregs of their cheap chianti and followed us out. It was good to breathe in the icy December air. And, believe it or not, George wasn’t kidding. He did live just around the corner from the pub. In Red Lion Yard, in fact. In a huge double-fronted house, the only double-fronted one in the Mews.

I remember thinking, “Blimey, if this guy owns this bit of exclusive Mayfair real estate, he must be loaded!”

Ming must have read my thoughts. She raised one of her heavily penciled black eyebrows at me as George, with his back turned, emptied all his pockets in an effort to find his keys. He gave up in the end and rang the bell.

The door was opened by a middle-aged man who smiled and beckoned us in.

George was holding my hand so the stranger ignored the others and addressed me.

“Evening, Miss.”

“Oh, this is Larry, Larry Horn!” George said. “Larry this is…is….” He blushed and guided the wayward lock of hair back into place. It had obviously just dawned on him he hadn’t even bothered to ask my name.

“Caroline,” I laughed. “And this is Ming, David, Camilla, Liam and Andrew.”

“Welcome,” Larry grinned. “Come inside, it’s cold. I’ll fix you all something to drink!”

We spent the rest of the night sipping hot milk and discussing art. This appeared to be George’s favourite topic. I discovered we had one thing in common – our preference for figurative art and our distaste (in his case) and disinterest (in my case) for abstract. But while my feelings were based purely on unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge, George’s were based, it seemed, on a lifetime of interest and research. In fact, he told us, he used to own an artists’ colony in the Santa Monica hills and now he was writing a book about art.

“Abstract art is rebellious and anarchic,” he claimed emphatically. “It’s puzzling to me, yes, even upsetting. It doesn’t draw me in. It doesn’t seduce me. And that’s what art’s supposed to do, wouldn’t you agree?”

“But, surely, art is supposed to be daring and rebellious?” my artist friend Liam swiftly responded. “Art should always be breaking boundaries.”

“Yes, I agree,” said Camilla, Liam’s girlfriend, who had just landed a job at the Royal Academy. “If not, we would never have progressed from the classical period. Look at Turner. He was very abstract for his time. He broke boundaries. He continuously challenged what was acceptable in his day.”

”And we would not have had the likes of Van Gogh, Bacon, Pollock or Picasso!” Liam added.

“Picasso is a particular bête noire of mine,” George responded quietly but emphatically. “His abstracts are ugly and unethical!”

“There are very many in the art world who would not agree with you,” I chipped in.

“They may not agree with me,” George said, “But I have my reasons. And they are all outlined in my book.”

He strolled over to the large walnut desk, picked up a much-thumbed typewritten manuscript.

“Here,” he said, handing it to Liam, “I’m still working on it. Read it and let me know what you think. Hopefully it will be published next year to coincide with my museum opening.”

There was a moment of silence as we all looked at each other, probably thinking the same thing. This guy was opening his own museum in New York. He really must be loaded.

Around 2am we all squeezed into George’s shiny black Rolls and Larry drove us home.

“He must have singled me out at the pub,” I whispered to Ming in the back seat, “I’ve no idea why.”

“He fancies you,” Andrew piped up, “it’s pretty damn obvious!”

“For heaven’s sake,” I said, “He’s a good thirty years older than I am!”

“What difference does that make?” Liam laughed.

But it’s true, there had been something about George’s relaxed manner, his lopsided smile, his disheveled look and even that stubborn lock of silver hair that refused to stay put that attracted me to him too.

We spent the rest of the drive home trying to guess who this mystery man was. None of us yet had a clue. And even when we asked Larry, he wasn’t saying anything.

“Well, he had a few photographs around. One with Sophia Loren. Another with Doris Duke. So he must be quite well known.” Camilla said.

“And playing tennis with Pancho Gonzales, he must be a pretty good tennis player!” Andrew said. “My Dad works at Wimbledon, he’s met Pancho Gonzales.”

“And did you see the one of him with Salvador Dali too,” Liam piped up from the front passenger seat.

“Yes, and another one with Charlie Chaplin,” Ming said. “I wonder if he’s friends with them all.”

We only found out from the newspapers the next day. Ming called me before breakfast. Very unlike her, I thought, after a night out she usually can’t be disturbed until lunchtime.

“Did you see the Express today?” she asked breathlessly. “It’s him!”

“Who? What are you talking about?”

“Him. George!” she said. “Except he’s not George. Well, he is. But he’s George Huntington bloody Hartford! Looks a lot younger in the photo here. But that’s who he is. It says he’s one of the world’s richest men, he’s a fucking multi-millionaire!”

Ming’s voice was rising to a rapid, uncontrolled crescendo. “He owns everything. A Hollywood theatre. An artists’ colony. A grocery chain. An island. A yacht. Famous paintings. He has houses all over the bloody world! And, like he said, he is building a bloody museum in New York to house his collection of art.” She hesitated for a second to catch her breath and then added, “has he called you?”

In fact, he had. After packing us all into his Rolls at 2am, he had called half an hour later to make sure I’d arrived home safely.

“Sweet dreams,’ he had said. “I’ll call you tomorrow.”

“Well, yes he has,” I replied to Ming, somewhat in shock.

“Are you going to see him again?” It was obvious Ming wanted me to reply in the affirmative.

“I don’t know, Ming. I guess. If he calls me I might.” I said hesitantly.

“Oh, he will!” Ming was emphatic. “Let me know as soon as he does, OK?”

As soon as she put the phone down, I flung on my clothes and headed out of the door, ran down Lower Belgrave Street and dived into the nearest newsagent. I picked up a copy of the Daily Express, turned to the William Hickey page and there, just as Ming had said, was a photo of George (or “Hunt”, as he actually preferred to be called) and a long piece about his being in England without his wife, the model Diane Brown, for Christmas and New Year, investing in a few paintings and finding a publisher for his book on art.

I started walking back towards Eaton Square. I was so engrossed in reading that I almost collided with a flower delivery man from Pullbrook & Gould on my doorstep.

“You live ‘ere?” he asked. “I’ve been ringing the bell.”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Caroline Kennedy, is that you?”

I nodded.

“I’ve got a delivery for you.” He shoved a piece of paper and a chewed pencil into my hand and walked back to his parked van. I watched him open the back doors and extricate the largest bunch of flowers I had ever seen.

Good God, I thought, I don’t have any 8ft tall vases.

His entire face and body obscured by the immense bouguet, the delivery man asked where he should put it.

I unlocked the door and told him to lay it on the black and white tiled entrance floor. There was nowhere else to put it. I signed the piece of paper and closed the door behind him.

Now, how was I going to explain this to my mother and stepfather? I bent down and plucked the note from the cellophane wrapping.

It read: “Caroline, I think we are going to be friends for a long time, tenderly Hunt.”

“Tenderly?” I thought. “Who on earth writes ‘tenderly’?”

And then I remembered, I had picked up a book from the side table next to his sofa the night before. It was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Tender is the Night”. He must have watched me thumbing through it.

The flowers ended up in my bathtub and then later in the day, at my mother’s suggestion, I dropped most of them off at St. George’s Hospital in Belgrave Square.

So, I thought, Hunt was married. That fact resolved one thing in my mind. There would be no affair, if that’s what he was hoping. And I actually came out and told him so, in no uncertain words, in the back of his Rolls on the way to see “Hamlet” at the National Theatre that evening.

“So, Caroline, you don’t drink. You don’t smoke. So what do you do?” Hunt squeezed my fingers and his face broke into a mischievous grin.

“Well, I’m not going to bed with you, Hunt, if that’s what you’re hoping!” I blurted it out but immediately realized the words sounded foolish.

“I’m sorry. But I don’t have affairs with married men,” I added.

“Then you’ll never know what you’re missing!” he smiled and squeezed my fingers again.

I shrugged my shoulders. “I guess not!”

He leaned over and kissed me, softly.

“I promise I will never try to make you change your mind. OK?”

I nodded. “Thanks. I appreciate that.”

“I’ll actually enjoy it. It will be different, even refreshing for me. But I’m warning you, you will read a lot of stuff about me when you come to New York. Some of it true. Some of it not. You can believe what you like. But one thing that is certainly true, I have had more affairs than I can remember. I’m a bit of a devil that way, I admit. But with you, it will be different.”

I smiled. For some reason, I believed him.

“Just promise me one thing. Please don’t tell anyone we’re not having an affair,” he joked, “my reputation would be ruined!”

He laughed out loud and the wayward lock of hair fell over his eyes.

“And if I tell people we are having an affair,” I answered, “I assume it will be my reputation that will be ruined!”

“A lose-lose situation!” he said. “But, don’t worry, we’re tough, we’ll survive!”

As soon as I arrived in New York, Hunt started inviting me out on a regular basis. He seemed to enjoy my company and we shared a passion for reading and writing. He wanted to become known, not just for his wealth, nor for his world- class art collection, nor even for the museum he was building in New York but he wanted to be accepted as a serious writer. He wanted to write the quintessential American novel.

I loved his enthusiasm and his belief in himself. I encouraged him to a certain extent. But inside I felt he always knew it was unlikely to happen.

Unlike our shared taste in art, our taste in writers and playwrights differed quite dramatically. I loved the moderns – Truman Capote, Tom Wolfe, Harold Pinter, Joe Orton and Tennessee Williams. He rejected them in favour of the classics – Tolstoy, Dickens, Conrad, Hugo and Shakespeare.

“One day I will write a novel that will make the critics rave!” he pronounced. “Honestly, Caroline, I will!”

“But surely you must know that great writers rarely spend their lives in gilded cages?” I said.

“You’re suggesting I live in a garret?” he laughed.

“If you want to write like Dickens,” I suggested, “you may need to experience or, even witness, real life more than you do.”

We were sitting, at the time, in the sumptuous living room of his Beekman Place duplex on the East River.

“I mean just look at this place. You are insulated from real life up here. You live in a vacuum. You were brought up on a vast plantation in South Carolina where you were isolated from the real world. You move in privileged circles, El Morocco, the Four Seasons, Biarritz, Monte Carlo, your Paradise Island resort. You only meet people who move in the same circle, who live privileged lives like you. Where is the grit for a novel in that?”

“How about F. Scott Fitzgerald?” he asked. “He came from a wealthy background like me. He wrote novels about people like me, and people like him, who lived in gilded cages. Isn’t he now considered one of the 20th century’s greatest writers?”

I couldn’t argue with that. My naïve, or childish, assumption that all great artists had to suffer in order to produce great art had been instantly demolished.

True to his word, Hunt did take me to El Morocco where he ordered his customary glass of milk and we were photographed by the paparazzi. I was the “mystery woman” on Huntington Hartford’s arm, in the Suzy Knickbocker column the next day.

He also brought me to his museum on Columbus Circle before the official opening to show me the collection of paintings that would be on view there. And he gave me a personal invitation to the opening later in the year.

And Hunt was there visiting me, in the studio above Carnegie Hall that I shared with my new boyfriend, Joe Dever, the society columnist of the World Telegram & Sun, when Richard Avedon dropped by and decided to take some photos of me. Avedon was filling in time while waiting for his favourite model, Veruschka, to show up for a Vogue cover photo shoot. Before he left, Hunt begged a couple of the polaroids of me from Avedon and stuck them in his wallet.

“Now I’ll never be without you!” he winked as he kissed me goodbye.

Hunt was a complex character. He talked often about his childhood, his domineering mother and his lazy, distant father.

“Early on,” he said, “I realized I wanted to escape my mother’s clutches. She tried to dominate everything I did. She was dead against me going into the family business. She asked why I wanted to be a grocer! So I did it, just to make her mad.”

“How did she respond when she found out you’d gone against her wishes?” I asked.

“She went completely insane,” he replied.

And then, mimicking her voice, he said,

“‘No son of mine is going to work for a grocery store!’ She even confronted my two uncles who ran the business and told them to fire me immediately!”

He smiled at the memory.

“The “grocery store” she referred to,” he explained, “was, at the time, the second largest corporation in America, after General Motors! Built up by my grandfather and uncles.” He laughed and shook his head. The unruly lock of hair fell over his eyes.

“My mother could be very formidable when she wanted to be.”

“What was their reaction?” I asked.

“They responded in the best way they could. My Uncle George said, ‘Henrietta, it is not beneath your dignity to accept very large sums of money every year from the grocery store, as you call it. But then you say it’s not good enough for your son to work here? Does that not strike you as somewhat hypocritical?’”

Hunt started to laugh again.

“And then, to add to my mother’s discomfort, they told her, ‘we could, of course, cut off your income, if you feel it’s beneath you to receive it?’”

“How did she react to that?” I asked.

“She went out and bought a very large piece of land in the Hamptons, I’m not kidding! I think she was scared they really would take her money away.”

Hunt’s eyes were twinkling. He was enjoying this.

“She said she bought it for me. But the real reason she bought was to be accepted by the Long Island crowd and to boost her chances of being included in the Celebrity Register! She was a real snob!”

One night Hunt brought Joe and me downtown to a seedy nightclub near 42nd Street.

“There are three people there I want you to meet!” he said. He refused to tell us who they were despite my pestering him all the way there.

All he would say is, “They’re expecting us!” and “You’ll enjoy their company. You’ll be able to write about them some day!”

He was right, of course. The three people who were waiting for us, our dinner companions that night, were none other than Francis Bacon, Tennessee Williams and Salvador Dali with his two pet ocelots on leashes.

“I’ve commissioned Dali to do a painting for my museum,” Hunt said by way of introduction, “It’s called The Discovery of America. And today we installed it right in the centre of the foyer so it will be the first work of art people will see as they walk in. I love it! You’ll have to come and see it for yourselves!”

Dinner with Dali was, as you may imagine, animated. His sense of mischief and his longwinded stories about his life and his art eclipsed any other conversation. It was evident he enjoyed being the centre of attention.

It dawned on me then I could actually introduce them all to a part of New York’s nightlife that was probably unfamiliar to them.

“After dinner why don’t we go to the Scene?” I asked. “I know the owner, Steve Paul, he’d love you all to come!”

So, later that night our motley crew squeezed ourselves into Hunt’s Rolls and Dali’s limo and drove the few blocks up to 8th Avenue and 46th Street.

As he was accustomed, Hunt got out of the car first and, without even acknowledging the long queue waiting outside the club, went straight up to the bouncer and, in his quiet but commanding way, asked to be let in. The bouncer, Ted, who I knew pretty well, held him back.

“Sorry, Sir! We’re packed tonight. And there’s a queue!”

I waited a while for this to sink in. It may well have been the first time in Hunt’s life that he was prevented from entering any establishment.

To put him out of his misery, I got down from the car and approached Ted.

“It’s OK, Ted, these people are my friends!”

Ted broke into one of his rare smiles.

“Oh, that’s alright then,” he chuckled. “How many are you?”

“Six,” I replied. And, as an afterthought, “and a couple of ocelots!”

Even poker-faced Ted looked taken aback.

“Excuse me?”

“Yes,” I grinned, “Mr. Dali never goes anywhere without his ocelots. I assure you, they’re perfectly well behaved. I hope that’s OK with Steve!”

At this point, people in the queue started fidgeting. Here was a group of people who had arrived late and were gatecrashing their way in. Several of them started complaining quite loudly, obviously intending us to overhear.

But, with his entrance timed to perfection, Salvador Dali, swathed in a floor-length black coat and his customary wide-brimmed black hat, swept from his limo, with his two ocelots in tow.

The crowd fell silent and then surged forward towards him, flinging pen and paper at him, begging for his autograph. Behind him, Francis Bacon and Tennessee Williams, stepped out of the limo unrecognized.

Ted then reappeared from the basement club with Steve Paul who greeted me and there, on the 8th Avenue sidewalk, I introduced Steve to my evening’s companions.

Steve, who was used to celebrity musicians, was evidently not so used to artistic and literary ones. For the first time since I knew him, he was almost tongue-tied.

He shook his head and whispered to me,

“I’m in awe, Caroline. I really am.”

I had to agree that I was slightly in awe as well. As a fledgling writer, meeting Tennessee Williams that night was a heady experience for me. He had always been my favourite playwright. And, although he was known as a reticent and very private person, he had opened up a little over dinner during a brief pause by Dali. He had told Joe and me he was about to go into production for his new play, “The Gnadiges Fraulein”. He invited us to the opening at the Longacre Theatre later in the year.

“I might just come over for that too,” Bacon had chipped in, “if it’s after my Paris show. And, perhaps, who knows I could even sell another painting to MOMA this year. ” He grinned. “And for a better price this time!”

“If you don’t mind me asking,” I said, “how much did they pay for your painting?”

Bacon grimaced.

“Well, it was about fifteen years ago, in 1948, they paid me the princely sum of around $500!”

“Perhaps, I can offer a little more!” Hunt piped up. He had been listening carefully to the conversation, taking notes, as he so often did.

“Perhaps, I can commission a painting for my museum.”

Knowing Hunt’s taste in art, I silently wondered whether Bacon’s paintings really appealed to him or whether he was simply being polite. But, as one of the world’s richest men, Hunt was so used to just buying things on a whim, at whatever the cost, that for him to acquire a Francis Bacon oil painting was no different than for me to go out and buy a box of Kleenex tissues.

During my first few months in New York, I often wondered why Hunt had never pushed me to have an affair with him.

“I gave you my word,” he said by way of explanation, “And, anyway, you’re not really my type. Besides, I told you when we met that we would be friends for a long time. If we had an affair that probably wouldn’t be possible.”

I found out later he wasn’t kidding when he had told me about his many affairs. The newspapers were full of them. And from what I read I realized he was right. I definitely wasn’t his type. I never had been. Hunt had a Henry Higgins nature when it came to sex. He liked to pick up hat check girls, waitresses and eager young models and mold them into beautiful society women, worthy of becoming entries in the Social Register.

“With you,” he joked one day, “I just never had the right material from the start.”

“Correct,” I laughed. “My blood is far too blue!”

I asked him once, “Aren’t you worried any one of these girls could get pregnant?”

Hunt laughed. “That would be a miracle,” he replied, “I’ve had a vasectomy, just for that very reason!”

And, true to his word, we did stay friends for a long time. He was right about that too. And when I was away travelling he would write to me. Proper letters in his scrawly handwriting. Letters that I kept along with a sheaf of other letters from family members, friends and admirers over the decades so that one day I could mull over them, reread them and be swept back to various moments in my life, long since forgotten.

Sadly, a warehouse fire in Tottenham, north London, that housed our family’s effects swallowed them up recently. So I have had to rely on my memory.

I left New York in 1967, to work for the BBC News in London. Hunt was in tears when I saw him to say goodbye. His illegitimate son, Buzz, the son he had always refused to legally acknowledge as his, had just committed suicide from a gunshot to the head.

“I should have recognized him,” Hunt sobbed. “I should have done more for him. He always wanted more. But we never knew each other. I only learned of his existence when he was in his teens.”

I didn’t how to respond. It was a fateful decision, we both knew it, a decision that Hunt would have to live with for the rest of his life.

I saw him briefly for the last time in London in 1971.

It was obvious he was still suffering from Buzz’s death and also from the loss of a very large portion of his wealth.

He was, he admitted, down to his last $30 million. Gone was the artists’ colony in the Santa Monica mountains. Gone was the Huntington Hartford Theatre in Hollywood. Gone was the Huntington Hartford Museum on Columbus Circle. Gone was his Paradise Island Resort in the Bahamas. Gone was his yacht, the Joseph Conrad. Gone was his art magazine, “Show”. And, on top of all this, gone was Hunt’s innate sense of fun. Gone was the freedom to do whatever he wanted. And gone was the belief that he could leave an enduring legacy of his patronage to the arts.

He took me back to Annabel’s that night and, over four scoops of marmalade ice cream and two glasses of milk we reminisced.

That night he already sounded to me like a man who had given up. He was not the Hunt I remembered. He was not the Hunt I knew. And he no longer appeared to be the Hunt I had loved all these years as a friend. Something about him had radically changed. And, sitting on the corner banquettes at Annabel’s, I realized our relationship had come full circle.

“I’m still working on becoming the world’s greatest writer,” he said jovially. But this time he said it without any pretense of self-belief, without a shred of conviction and without even a hint of passion. He knew, and I knew, it was never going to happen.

“I do have a story to tell, don’t I?” he asked as he twisted the half-empty glass of milk in his long fingers.

“Yes, you certainly do,” I said. “In fact, few people have a better one. But just remember, when you write it, please don’t forget to include the episode of the ingrown hair! Nobody will believe it, except me!”

His eyes started to well up as he raised his glass to me. He signaled to the waiter for the bill.

“You know what, Caroline?” he laughed. “Some things never change. A glass of milk here still costs more than a glass of milk at El Morocco’s! And if you don’t believe me, you’ll have to come back to Manhattan with me and see!”

That was the last time I saw Hunt. Soon after his return to New York he simply vanished without trace. It took almost a decade before he was discovered by his daughter Juliet. Emaciated, drugged and enfeebled, Hunt had spent several years forcibly locked inside a house in upstate New York by a crooked attorney who sold off his entire painting collection, his photographs and his documents relating to his businesses.

There, in his own gilded cage, he was kept a virtual prisoner, his only company for almost a decade – a handful of hangers-on who lived off his fast-diminishing income and several drug addicts who befriended him because they needed a roof over their heads.

After a long history of bad deals, ruinous investments and avaricious “friends”, Hunt had finally handed over control of his life to others.

But, if only he could see it, I thought, Hunt was actually living the very novel he would never write. If his instincts had been intact he would have realized that his own downfall had the all the ingredients of a compelling story, chronicling the self-destruction of a once immensely rich and powerful man.

The irony was that the quintessential “riches to rags” narrative, if only he had the will and the strength to write it, might well have catapulted him to the ranks of “greatest living author”, something he so badly wanted all his life.

But, sadly, by this time, his mind was so addled by drugs, his body so crippled by inertia and his ability to take back control of his life so completely squandered that he was powerless even to take out his notebook and scribble down the words, let alone use a typewriter.

I can still hear him now saying, “I do have a story to tell, Caroline, don’t I?”

And I would answer, “Yes, Hunt, you have an incredible story to tell. Now, just sit down and write it!”