I arrived in Manila in late June 1968. My initial impression was of a sprawling, bustling and filthy city, its downtown roads continually jammed with impatient, honking traffic. Dilapidated, overloaded buses belching diesel fumes, vied for space with garishly painted and

ingeniously adapted World War II jeeps, known as jeepneys. A motley assortment of decrepid taxis ploughed their way through the potholed roads alongside ramshackle trucks, flimsy bicycle rickshaws and sleek air-conditioned limousines, their glass darkly tinted to keep out the prying eyes of the endless hordes of curious people thronging the streets and sidewalks outside. Amidst this chaos, emaciated stray dogs, cats and rats scavenged for scraps of food among the numerous piles of discarded fly-infested rubbish dumped outside countless fast-food restaurants. And, circling the churches, limbless beggars and able-bodied scroungers competed with candle sellers and vendors of religious artifacts for a monetary offering from the passing congregation.

In contrast, on Roxas Boulevard, stretching the full length of Manila’s eastern shoreline wasevidence of Imelda Marcos’s nascent building programme, or “edifice complex”, as it came to be known. The Cultural Centre was to be the first of many multi-million dollar buildings set on 21 hectares of reclaimed land stretching far out into Manila Bay. It was built with funds brazenly extorted from charitable foundations, the Philippines treasury, the war reparations chest, wealthy businessmen and intimidated bank presidents, setting a successful fundraising precedent for all her projects to follow over the next two decades. Now, in only her third year as First Lady, Imelda was already, it appeared, an enthusiastic convert to the doctrine of absolutism. No one was permitted to challenge the methods she used to make her mark on the city she considered was hers by Divine Right. Like her husband Imelda had come to believe she was answerable only to God. Yet, at this early stage, she was still naively unabashed by her own unscrupulous methods of obtaining money to finance her pet projects. She declared to the media, “I am Robin Hood. I rob the rich and give to the poor.” Her explanation to myself and my friend, her niece Betsy Romualdez, was far more bizarre, “Building the Cultural Centre,“ she explained, without batting an eyelid, “will reduce juvenile delinquency.”

But just how it would succeed in doing this, she couldn’t or wouldn’t divulge. The month I arrived in town the gossip was that Imelda and her eldest daughter, Imee, were in New York on what was to become the first of many notorious and increasingly avaricious shopping sprees. The local newspapers, still free from the rigid censorship that would soon be imposed by the President, were having a field day. They reported the pair spending around $100,000 a day at Tiffany’s, Harry Winston’s and Sak’s Fifth Avenue. In less than eight weeks, the papers said, mother and daughter had managed to part with $3.5 million on jewels, clothes and gifts at a time when unemployment back home was escalating at an unparalleled pace and the majority of the population was struggling to pay for the bare necessities of everyday living. The air of anarchy that prevailed on my arrival in Manila was tangible. But, even as a

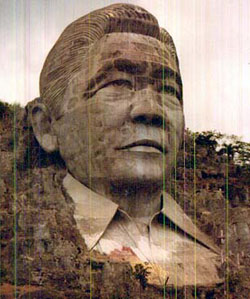

newcomer, it was obvious to me that it was covertly being encouraged by President Marcos who was already hatching embryonic plans to remain in power in perpetuity. In the summer of 1968 only a handful of very loyal cronies was privy to his secret, codenamed Oplan Sagittarius. Marcos’s most persistent worry was that he would lose the presidential election in 1969. He had convinced himself that the only way to remain head of state would be to either rewrite the constitution to approve a parliamentary form of government or, more dramatically, seize emergency powers and declare martial law. The first choice, changing the political system, he made possible through wholesale vote buying. Delegates to the Constitutional Convention and the judges who would later have to endorse the vote through legal channels were wined and dined at Malacanang Palace and then handed envelopes stuffed with hundreds of pesos with promises of more to come. The second option was more difficult. For, in order to establish a need for martial law Marcos knew that a climate of fear, rumour and innuendo had to be established over a prolonged period of time. A communist threat, still in its infancy in 1968 and claiming no more than 300 followers had to be proved to a much more powerful menace capable of overthrowing any democratically elected government. And the Americans would have to be sufficiently convinced of this to give their wholesale backing to his plans. So, to help maintain this climate of fear, bombs were exploding all over Manila, mainly in government buildings at night, in order to maximize fear among the population but to minimize the numbers of casualties. The population, already wise to Marcos’s ambitions,blamed the President and he, in turn, blamed the Communists New Peoples’ Army(the NPA). At the same time street crime was rampant, armed burglaries were routine

and handguns were a must for all those who cared about their own self-preservation. Student demonstrations, until then a typically good-humoured combination of fiesta and political rally, were becoming increasingly serious and were met with brutal resistance. Peaceful protests outside the American Embassy on Roxas Boulevard against Filipino involvement in America’s war in Vietnam were dealt with likewise.

Law and order was breaking down, the economy, once the pride of Asia, was in tatters and the standard of living, once envied by other south-east Asian nations, was now comparable to some of the most impoverished countries in the world. In my first week an earthquake rocked the city adding to the sense of cynicism and hopelessness. It measured 5.6 on the Richter scale, devastating parts of downtown Manila. Some English acquaintances I had just met, exchange music students from the London Philharmonic Orchestra, were injured when the wall of their rented house collapsed. One of them, a young man of 25, ended up paralyzed for life. It was a somber first-hand experience of the havoc invariably caused by the notorious “ring of fire”, the earthquake zone circling the islands and coastlines of the Pacific Rim. A new apartment block, the Ruby Towers, entirely concertinaed in the quake, its four floors crushed into one, leaving many dead and scores

seriously injured. But, within a day, before the law could catch up with them, the developers, friends of the President, had fled to Hong Kong to avoid prosecution. In their absence it was proved they had cheated on the quantities of cement they used to construct it. This was not unusual. Graft, kickbacks and bribery for all manner of reasons were commonplace in the Philippines and the prime examples of all these were being carried out by the highest office in the land, the Presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. In the summer of 1968 the people in the Philippines, Asia’s only Catholic country, had little else they could do but pray for better times ahead. But, despite fear and mayhem on the street, Manila’s social and artistic scene was thriving. True to her word, my friend, Betsy Romualdez, introduced me to her wide circle of friends. I soon discovered that despite her long absence from the Philippines, she was still considered

very much a leading light of the city’s cultural activities. After all, she owned the “Indios Bravos” cafe, the only mecca at that time for artists, writers, poets, journalists, photographers, dancers, actors, musicians and sculptors to discuss their work, plan their next shows and catch up on all the latest literary, political and social gossip. Added to these was always the odd sprinkling of foreign embassy personnel hoping to be part of the “action”, overseas tourists looking to experience some “local colour” and presidential aides and politicians either wanting to be considered “hip” or, more often than not, spying for the government. “In Indios Bravos,” Betsy told me my first day in town, “you will find that East truly meets West.” This was no idle boast by the café’s proud owner. For, it’s true to say that, on any given night, in the salon-like atmosphere she had created, you could sit down under the tiffany lamp at the long main table that sprawled across the centre of the room and join in an animated discussion about contemporary literature with the U.S. Cultural Attache, Jack Crockett, award-winning novelist and short story writer, Nick Joaquin and the Philippines’ high priestess of poetry, Virginia Moreno. Or, alternatively, you could find yourself in one of the café’s dimly-lit corners with the British Ambassador, Sir John Addis, local archeologist Robert Fox and anthropologist Dave Baradas, totally absorbed by their talk of the latest pre-historic discoveries unearthed in the Tabon Caves, off Palawan.

Or, entirely unsuspecting, you might even find yourself sitting at a small round table just inside the main entrance with a tall, polite, elegantly dressed Swiss German who would proceed to charm you, over a glass of iced calamansi juice, into revealing just a little too much information about yourself and the political leanings of the café’s principal habituees. But this, you would soon find out, would be a big mistake as this particular table was the favourite spot of President Marcos’s right hand man. And the person you had been chatting to so freely, so idly and so innocently was far from the kindly, respectable Swiss gentleman you had imagined him to be but on the contrary, he was the much despised, much feared, highly vindictive presidential henchman, General Hans Menzi himself. And some nights you might notice that, if no one accepted his invitation for a drink and a friendly chat, Menzi would be content just to sit for hours alone, sullen and vigilant, dutifully keeping tabs on the many comings and goings, all of which he would report back later that night to his conjugal masters. Not surprisingly then, these visits to Indios Bravos by the General were frequently succeeded by a drugs raid by the police force most loyal to Imelda Marcos, the dreaded Manila Metrocom.

At Indios Bravos, too, you could choose merely to table hop, perhaps stopping to sip the locally-brewed San Miguel beer and exchange the latest gossip at one table with a group of journalists, or taste some local dish of fresh lumpia and tap your feet to the Beatles’ “Hey Jude” with a group of dancers at another, join in an ad hoc art class or poetry reading with some of the café’s artists and poets at another, or, simply, just chill out, relax and smoke a joint alone in a corner. In retrospect, then, it’s true to say that no description of Manila’s cultural scene during the 1960s would be complete without mentioning the watering hole that the Indios Bravos cafe became during that politically turbulent and culturally explosive decade.

“The café is named after an organization of expatriate Filipino artists, writers and nationalists based in Paris and Madrid in the late 1880’s,” Betsy told me as we made our way there on my first evening. The novelist and academic, Dr. Jose Rizal, created this nationalist movement with the purpose of fighting the oppressive Spanish colonial government for tax, education and civil rights reforms on behalf of the indigenous Philippine population. Rizal had taken the name “Los Indios Bravos” for his group after attending the American stage show, “Buffalo Bill” in Paris. As the curtain came down Rizal couldn’t fail to notice how the French audience immediately rose to their feet as one and loudly applauded the American Indians for their courage and bravery, shouting, “Les Indes courageux, comme ils sont braves, les Indes courageux!” Since the Spaniards in Manila referred derogatorily to the local population as “Indios”, Rizal wisely thought, that by calling his nascent nationalist movement, “Los Indios Bravos” he would turn their insult into a title of pride, respect and honour.

Most of those expatriates calling themselves “Los Indios Bravos” eventually returned to the Philippines and joined up with the local revolutionaries, the “katipuneros” fighting for independence from the Spaniards. Many were destined to become martyrs to their own cause, including Jose Rizal. But, although he supported the revolution, he was not convinced the katipuneros had enough guns and ammunition for it to succeed. His own fight, therefore, was directed more against the corrupt Spanish clergy in the Philippines than incitement to armed rebellion. And, following publication and seizure of pamphlets he’d written lambasting Spanish religious institutions in his country, he was exiled to the island of Dapitan for four years. Later the Spaniards moved him back to Manila, to solitary confinement in Fort Santiago, to await public execution. Rizal’s death by firing squad on 30 December 1896 at Bagambayan only served to confirm his place in the history of the Philippine insurrection and contributed to his posthumous reputation as the country’s most celebrated national hero. But his death also served to fuel an enduring rumour about him that still prevails to this day. For it is believed by many that Rizal went to his grave without revealing a dark secret that, forty years later, would have apocalyptic repercussions across the whole of Europe and beyond – that it was he who was the biological father of a seven year old Austrian boy, Adolf Hitler. And, if a DNA test ever proves this conclusively, then it is true to say Rizal, despite his justified elevation to heroism in the eyes of all Filipinos, did no favours to the rest of the world. Betsy, as it turns out, was not only the high priestess of this new “Indios Bravos” but was also a well-respected poet and writer in her own right and, as such, was well connected in media circles. Within a week of my arrival I had done the rounds of Manila’s Tagalog and English language papers with her, met most of the current crop of writers, journalists, editors and publishers and had secured a weekly column in the weekend supplement magazine of the Daily Mirror. And, because of our nightly jaunts to “Indios Bravos” I was introduced to the “Who’s Who” of Manila’s artistic talent. All, without exception, seemed to welcome Betsy’s “hippie” friend from England and it didn’t take long for me to be accepted as very much a part of the Manila scene. “I’ll call you Caroline London!” the principal cartoonist of the Manila Times, Nonoy Marcelo,

announced when Betsy brought me to the newpaper’s downtown office on my second day. And true to his word, within a week, there I was easily recognizable as Caroline London, in my Ozzie Clarke robes, waist-length necklaces and flowing blonde hair, incorporated into Nonoy’s daily comic strip, “Tisoy”. And, later in the year, when “Tisoy” became a successful weekly TV series and, eventually, made into a movie, I was given a role in both playing myself as the English hippie, Caroline London. “And I’ll paint your portrait!” declared the prodigal painter, Fredirico Aguilar Alcuaz, recently returned from several years in Germany, when we met up in Indios Bravos one night a few weeks after my arrival.

In fact Alcuaz painted two very different versions of the same portrait, one ethereal and one robust, the former he gave to me, the latter he kept for himself. “I’ll take your photograph!” exclaimed top photographer, Frankie Patriarca. And, indeed he did. Not just one personal snapshot but, over the following year, more than enough photos of me to focus an entire one-man exhibition on very different versions of my face.

“And I’ll teach you some words of love in our native language,” Jose Garcia Villa, the Philippines’ internationally recognized poet, whispered enticingly in my ear one evening as he held court under the tiffany lamp at the top table of Indios Bravos. Believing the great poet was about to teach me some irresistibly seductive chat-up lines I made a conscious effort to listen, retain and mimic his exact words. I was, after all, I assured myself, being taught by a master not only renowned in his own country for his exceptional lyricism but also accepted as a foremost Modernist poet in his adopted city of New York. Later in the evening Jose made me feel confident enough to loudly declare, in my most resonant Shakespearean voice, to each of the assembled politicians, artists, journalists and diplomats in turn, “Balaktut ang titi mo!” At first there was a stunned silence, then everyone roared with laughter, all that is except for General Menzi who could be seen scribbling away gleefully in his notebook. I imagined it must have been my accent that had failed me and turned back to Jose for some coaching. I spent the next few evenings being tutored by the ever-attentive poet, repeating the same phrase over and over to him as I vainly attempted to perfect my Tagalog pronunciation. “You’re ready now to try it again,” Jose confirmed a few nights later. “Your accent is brilliant. Say it like that and no one will laugh at you, believe me!” He placed the trademark large silver medallion that hung heavily around his neck into my open palm, “Touch this for luck and all will go well tonight, I promise!” Thus, egged on by Jose and the rest of the Indios Bravos crowd, I again announced to every new man who walked through the doors that night, “Balaktut ang titi mo!” But the reaction to my romantic protestations of love, far from being received with blushes, smiles and kisses, was, inexplicably, no different than on my first attempt. In fact my words were greeted with derisive laughter or stunned silence each time. Nobody inside Indios Bravos was able to keep a straight face, not even the great poet himself who appeared to be enjoying my spectacular embarrassment. Some recipients laughed outright, others leered at me as though I had just materialised from a different planet, while others seemed distinctly offended by my words. It wasn’t until a week later, when Jose Garcia Villa had said his farewells and returned to his adopted New York, that Betsy finally broke the bad news to me. Instead of poetically declaring my burning passion to each of the men in turn, Garcia Villa had taught me to inform them, with as much seductive ardour as I could muster, that their penises were crooked. The laugh was definitely on me but it took me until my next encounter with the great poet, in New York in 1970, to forgive him and to appreciate the funny side of his practical joke. The result was that the insulting phrase spread rapidly around town and, from day one, I became a controversial figure in Manila. It remained that way for the rest of my long association with the country. To some I became a much-loved “honorary Filipina”, an independent young woman with no religious, political, social or sexual hang-ups who, during an era of enforced intimidation, fearlessly spoke or wrote her mind on any and all taboo subjects. While to others I turned into a hate figure, a detrimental example to all Filipina women, an undesirable alien, a person to be vilified in the media, castigated by the government and banished by the Department of Immigration and Deportation without delay. One Christmas night in 1968 Betsy, Henry and I entered the Indios Bravos café after a day out on a beach in Tagatay. From outside on the pavement I could hear Christmas carols blaring out from the shop fronts all the way down Mabini Street. “Dashing through the snow, on a one horse open sleigh…” I stopped in my tracks. Snow? Did I hear right? “Sleigh bells ring, are you listening?….” Sleigh bells? No, this must be a joke, surely? “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas…” A white Christmas? Here in Manila where winter temperatures rarely fall lower than 18%C? They can’t be serious! I looked at Betsy and Henry. They were chuckling at my expression. It all seemed so incongruous, so utterly absurd and, yet, so typically and so endearingly, Filipino. Here I was, a visiting writer in a paradise of some 7000 islands, soaking up the warmth of my first ever sub-tropical winter, surrounded by things I could only have fantasized about from the bleak, damp interior of the Edwardian apartment in London that I called “home”. Coral atolls fringed by crystal turquoise waters, palm trees rustling in a gentle Pacific breeze and endless miles of silver beaches reflecting the warmth of a mid December sun. And, yet, emanating from all brightly lit shops and restaurants the sounds of Christmas carols were wafting down Mabini Street. Pictures of Father Christmas, snowy beard, Nordic skin and twinkling blue eyes beamed out at us from every window. Christmas trees, covered in snowdust and wads of fluffy cottonwool, stood proudly in doorways. Even the prostitutes, pimps and cigarette vendors hovering outside the café that night – two nights before Christmas 1968 – were wearing tinsel in their hair and sprigs of plastic holly around their necks. Inside the café a real log fire crackled and burned. And even the conversation seemed no less bizarre. “Sure,” the poet Virginia Moreno said to me as I sat down beside her, “sure many Filipinos

believe if we become the 51st state of America then we’ll have white Christmasses.” Her tiny face peered out at me through the comical oversized spectacles that had become her trademark, My jaw dropped in undisguised disbelief. “But, it’s true!” she insisted, “Hindi ba, Nick?” She looked to Nick Joaquin, aka Quijano de Manila, the outspoken columnist of the Philippines’ Free Press, to back up her characteristically wild assertion. I was used to Virgie’s outrageous remarks by then and wasn’t about to be taken in yet again. But Nick nodded in agreement. “There’s a group here, Caroline, you must understand, who really are convinced that the Philippines will become the 51st state and,” he added, as he downed a seasonal glass of brandy in one swallow, “obviously, with American statehood comes snow!” I waited for Nick to smile, to nudge me in the ribs, to kick me under the table, admit he was

jesting, tell me how I gullible I was. It would not have been the first time he had made fun of me and it certainly would not be the last. But, no, this time he appeared deadly serious! At that precise moment, General Hans Menzi strode through the door. With all this talk of a White Christmas I half expected him to be trailing an icy blizzard and a sleigh laden with Christmas gifts in his wake. This tall, shadowy figure was formerly a Swiss army officer with a dubious past before he joined Marcos to become the much-feared eyes and ears of Malacanang Palace. Most of the regulars were in Indios Bravos on that night before Christmas Eve, including the American cultural attaché, Jack Crockett. Jack had become such a vital part of our scene that, like me, he had been bestowed the title, “honorary Indio” by the adoring café literati. But General Hans Menzi was never welcome. Mercifully, to date, he had been a fairly infrequent customer. His penchant for little boys had been well-recorded gossip around Manila for several years but rarely, if ever, had anyone dared broach the subject in public. To be caught voicing those rumours, whether in coffee houses or living rooms, the regulars told me, would be tantamount to treason. To even whisper them around Manila would be to risk one’s life – or, at least, one’s liberty. “So keep your mouth shut!” Virgie warned me as Menzi walked towards his regular table by the window. But, for once, Menzi appeared to be in the Christmas spirit, almost managing to force a smile in our direction. We had suspected for some time that the only reason the General ever visited the Café was to pick up one of the many young boys who loitered around outside the door every night waiting to call a taxi for the café’s customers as they left and hopefully to pick up a tip. Either that or Menzi was sent to spy on us, to report on the hippie drug scene of the Indios Bravos crowd to Imelda’s “thought police”. For both reasons it was always considered wiser to stay out of his way, for to annoy or displease him was to court personal disaster as many, including Betsy and Henry, would soon discover. So, on that Christmas night, we all smiled back amiably, if somewhat reluctantly. I noticed one young photographer even politely vacated his seat so the General could sit down at his favourite table next to a prodigal son, the artist Fred Aguilar Alcuaz, recently returned from several years in Germany. It was painfully apparent to those of us watching that Alcuaz had no idea who Menzi was and we didn’t have a chance to warn him. After raising a convivial glass or two of his favourite drink, Menzi leaned over towards Alcuaz and whispered, “Do you know where I can get any pot around here?” The chatter came to an abrupt halt. Some people froze on the spot. Others stampeded towards the loos to flush their own incriminating evidence down the one working toilet. Others tumbled over each other in their haste to catapult themselves out into the street. And, yet, others, not wanting to attract attention to themselves, nonchalantly stamped out their spliffs on the floor beneath their seats. Everyone fidgeted nervously, frantically attempting to secrete their half-smoked reefers under the table, stuff their Rizlas and hash into the upturned Tiffany lampshades, or wrap them up in paper napkins and flick them into the nearest wastebin. Even the waiters turned and fled to the comparative safety of the kitchen. They didn’t want to be around for any trouble. “White Christmas” had, by now, given way to the anti-Vietnam War carol, Simon & Garfunkel’s “Silent Night” But at that moment the needle jerked off track leaving Nixon’s compelling and haunting voice-over to splutter, grind to a halt and, finally, die. All eyes and ears swivelled towards Menzi and Alcuaz. None of us in the café could believe what we had just heard. As we all waited for Alcuaz to speak, the painter removed a pen from his top pocket and started scribbling an address onto a white paper napkin. We held our communal breath, waiting for the police to come bursting through the door to arrest the unsuspecting Alcuaz.

“There is one place,” the artist smiled into his disappearing whisky, “there’s a shop around the corner – on del Pilar Street – they sell pots, I mean terracotta ones, but…” he glanced down to look at his watch and we all did the same. It was almost midnight. “Yes,” Alcuaz continued, “I’m pretty sure it’ll be closed now but there might be one I know in Quezon City which will be open at six o’clock tomorrow morning! Do you need the pot urgently?” He scribbled down another address and handed it to the amazed General. None of us knew whether to laugh, cry, giggle or weep. Was Alcuaz just being very clever? Surely, he had been living in Frankfurt long enough now that he couldn’t be that innocent? Or could he? He must have known all about hash, pot, weed, grass, ganja, call it what you will? But no. It’s just possible he had no idea. I had got to know him quite well in recent weeks. I had been sitting for two portraits by him and I had come to the firm conclusion that he was just about the most socially naive person I’d ever met. That Christmas night Menzi, in all his misleading display of camaraderie, had chosen the wrong man. And now the bogus four-star general had been embarrassed in front of all of us. We knew instinctively what this could mean. Menzi was not about to forget such an humiliating experience. For certain he would exact his revenge – in his own way and in his own time. We would pay for Alcuaz’s innocence. This would mean Indios Bravos would, most likely, be raided soon. There was little doubt in any of our minds about that. It was just a question of when. And, yes, sure enough, a few days into the New Year, General Menzi’s belated Christmas

present arrived at Indios Bravos, not in the form of Santa’s sleigh bearing gifts, but in the form of the Manila Metrocom, searching for drugs. Betsy was about to learn that writing unfavourably about Imelda, even at this early stage, did not go unpunished. Betsy had often said to me that if you played by her Aunt Imelda’s rules she would smother you with love and largesse but, “if you crossed her or criticized her or saw her as, in any way, flawed, she would be an implacable foe.” That evening Betsy found out just what kind of a foe her aunt Imelda was prepared to be. And there was no doubting the raid’s concealed Christmas message from the First Lady. Like the sleigh bells, it rang out loud and clear to all the habituees of Indios Bravos. “Welcome to 1969. I shall be watching you!”

Reading some of your articles kept me informed part of Philippines History. I was born in 1971 and obviously I was such a baby when you are exploring the ins-and- outs of Philippines lifes and ways.

Your articles brought me back to some information from the past where I can now see in broader aspects the Philippines of today.

My eldest child, Elisar, was born in 1971 too. So his history of the Philippines is through my writings as well.

Reblogged this on Caroline Kennedy: My Travels and commented:

I thought this is relevant as many of the comments on the blogsite refer to Imelda and what I wrote about her. This is a chapter of my memoirs about my very first experiences in Manila and my thoughts on the Marcoses at the beginning of the Marcos Presidency.

Thank you, fascinating insight.

Wow, I just came across your blog and started reading your memoirs! I’m amazed by your vivid memory and description of late-1960s Manila and your good experience and acquaintance with luminaries in arts and politics (through your impeccable writing)! They’re as educational as entertaining! (I was born in 1977). 🙂

Thank you, Nathan, so glad you enjoyed it despite having been born in ’77! My youngest daughter was also born in 1977. Hope you enjoy the rest of my memoirs. I keep adding to it. So there’s so much still to write!

Thank you, Ms. Kennedy, for acknowledging me and responding to my comment! It’s fresh history (with a creative flair) from one’s personal perspective. That makes it more relevant to me since I know little about what it was really like back in those days and further raises my socio-political awareness, especially so that we’re not virtually far away from national elections. Yet I will also read the other interesting sections in your blog. 🙂

I am glad it helps you, Nathan, to get a new perspective on a particular period of the Marcos regime. I hope you enjoy the rest of the articles. One day I’ll get around to writing more!

Nostlagic! I was born in ’76 and I am really fascinated with the stories of the 60’s and 70’s. Hope to read more of your stories. Thank you and more power po.

everything you write about the philippines is relevant! most especially because it is an ‘outsider’s point of view (no disrespect intended) quite a few pinoys today are longing for the ‘quiet’ and ‘crime free’ days of the marcoses. not realising that those days were ‘quiet’ and ‘crime free’ because nothing negative was allowed on the press. now that family is again on the brink of power, holding key positions in the public sector. i can almost see you shaking your head in disbelief at the stupidity of some pinoys for putting them back in office. judging by this blog alone, i can safely say that you’ve lived a life in the philippines more ‘filipino’ than most of us native born ever could. thank you for sharing that life….

This is truly a lovely comment, Reggie. I’m very touched. Thank you for your appreciative words. And yes, you are right, I am shaking my head, more in puzzlement than in despair. However, thankfully, I think I can almost (almost) guarantee that Bongbong will not win the Presidential election. Or maybe that’s more wishful thinking than anything else! And, yes, again, I do feel very Filipina. And I am reminded again and again of that every time I go back to your country. Thankfully I still have a daughter who lives there so have a good reason to return. It’s always a special time meeting up with all my old bacardas, all of whom are still extremely talented writers, artists, poets, dancers, actors and musicians. It is a great treat for me to sit and listen to their views on the changing political, literary and artistic scene over the past few decades.

Hello, Miss Caroline!

My name is Aleina and I am currently working as a researcher for a documentary series for the centennial celebration of Philippine Cinema. I would like to ask if we could grab Ms. Virgie Moreno’s photo this blog entry.

If you permit, we would like to ask for your e-mail or contact so that we can give you a formal request letter.